Yaw Rate prediction for Formula One using onboard data

work done for Alfa Romeo/Stake F1 Team

This project was done during my internship at Alfa Romeo/Stake F1 Team, where I also completed my Master’s thesis (with Prof. Jean-Philippe Thiran of EPFL).

The goal of the project was to extract new trajectory data (mainly yaw rate but velocity as well) from the onboard footage of the Formula One cars. Indeed, each Formula One car has a monocular camera mounted on top, and thus race footage is publicly available. The idea was to use this footage to extract the yaw rate of the car at each frame, as well as the velocity. This data is crucial for the engineers to understand the cars’ behavior and improve/understand their performance. The performance of the algorithms were examined using the available telemetry, however the goal would be to generalize to cases where the telemetry is not available.

The project was divided into two parts: first extracting only the yaw rate from the footage using Visual Odometry methods (extracting the velocity in that case was not possible due to the scaling problem of monocular only cameras), and then using deep networks to predict the yaw rate and velocity from the footage.

Visual Odometry is the tracking of the camera’s movement in 3D space from a sequence of images. Two main categories arise: Direct methods, which estimate the motion directly from the pixel intensities, and Indirect methods, which estimate the motion from the features extracted from the images. The two mothods were tested. Both methods require 2D-3D projections, with the formula below, where s is the scale factor, f is the focal length, u and v are the pixel coordinates, c is the principal point and Xc, Yc, Zc are the coordinates of the camera in the world frame.

\[s \cdot \begin{bmatrix} u\\ v\\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} f_x & 0 & c_x\\ 0 & f_y & c_y\\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} R \mid t \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} X\\ Y\\ Z\\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\]Direct methods use directly the raw pixel intensities to estimate the pose, hence by taking a small window of previous frames, it would theoretically be possible to reproduce the current frame, for each of the previous ones, by knowing the intrinsics, extrinsics and 3D coordinates. For a point p, with R being the rotation matrix, t the translation vector, $\Pi_c$ a projection function and d the depth of the point, the projection is given by the formula below, where p’ is the projection of p in the image plane.

\[p' = \Pi_c (R \Pi_c^{-1}(p, d_p)+t)\]Therefore, the pose is a parameter of the projected frame and thus by minimizing the photometric error between each couple of frames, the pose can be estimated and optimized. The main advantage of direct methods is that they are more robust to textureless surfaces, as they use the raw pixel intensities. However, they are more computationally expensive and sensitive to lighting changes.

On the other hand, Indirect methods use features extracted from the images to estimate the pose. The features are usually corners, edges or blobs, and are tracked from frame to frame. Depth of features is estimated and added to a 3D map. Features are then extracted on the next frames and matched to the ones of the map and projected to the image (using intrinsics and extrinsic parameters). The 2D error is then minimized (Bundle adjustment) to optimize the pose.

The main advantage of indirect methods is that they are faster and more robust to noise or lighting changes, but they are less robust to textureless surfaces.

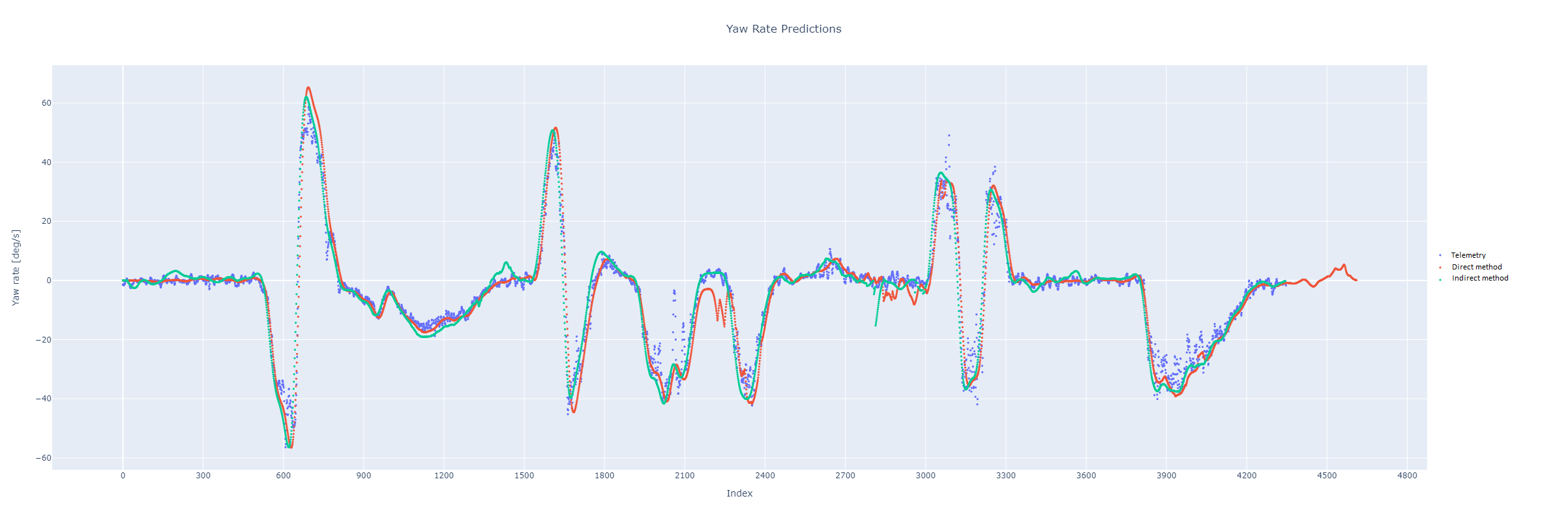

Both algorithms were run on the same lap, with the telemetry data of the car available. To filter out noise, each algorithm was run 10 times and the median was taken. The results were then compared to the telemetry data. The plot belows shows a lap where no one cars were in the FoV and during the day (“ideal setup”). Other more challenging setups were experimented and the results were quite promising, however due to the required discretion of working for a F1 Team, other plots were not included in this website (feel free to reach out to me if you want to see more results!).

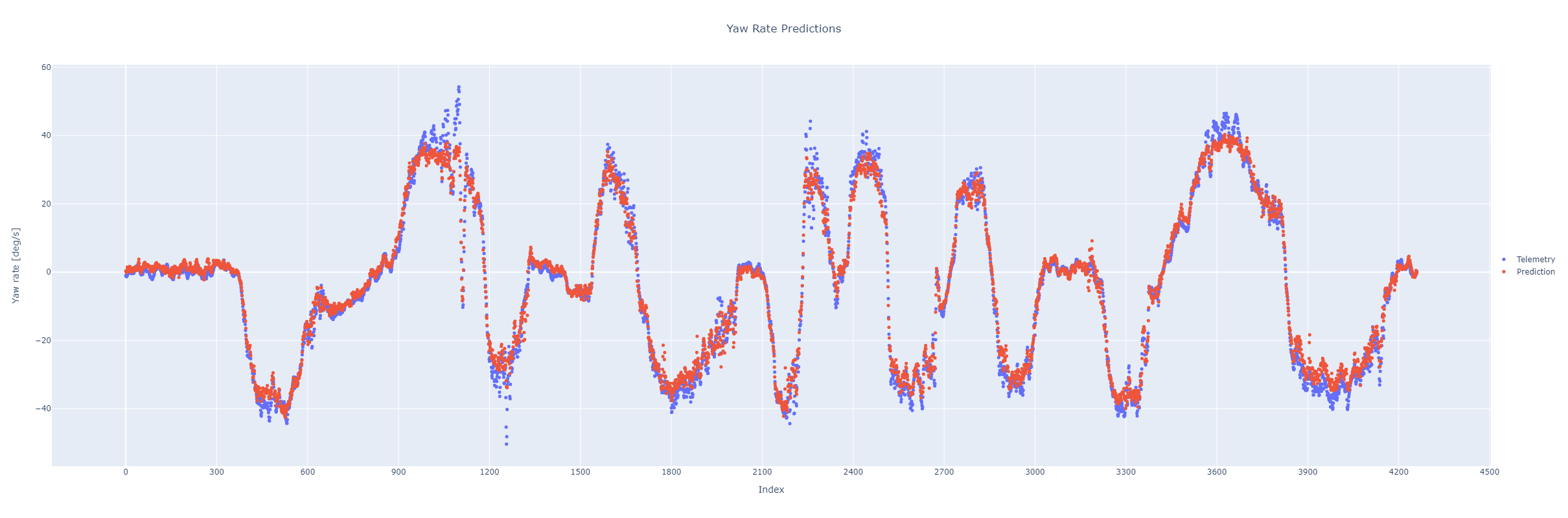

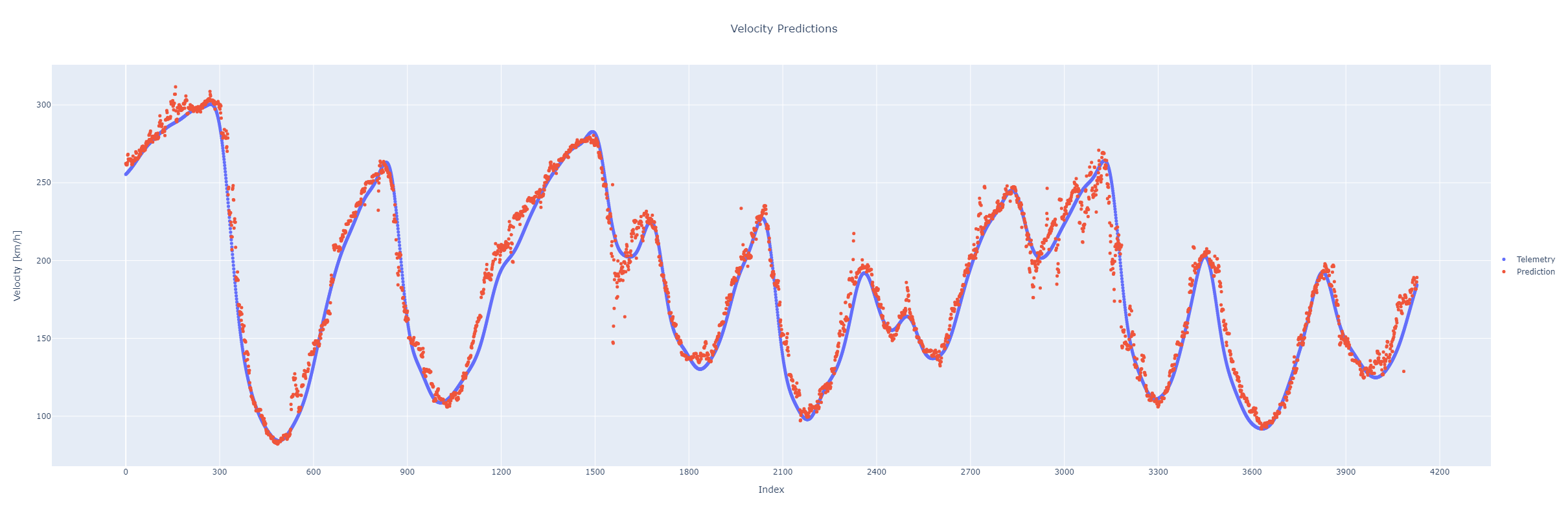

The second part of the project was to use deep networks to predict the yaw rate and velocity from the footage. The network would be trained in a supervised manner using the available telemetry data of one of our drivers, and tested on our other driver to evaluate the generalization capacities of the network. Several self-supervised opensource network were finetuned (with a new supervised loss), as well as a custom in-house network. The network performed quite well, especially when trained and tested on the same event. They also managed to adapt well to different events, night races and cases where competitors cars were present in the FoV. But once again, for confidentiality reasons, results were not uploaded (feel free to reach out though!).

The velocity predicted network was a bit less performant than the yaw rate network, as the scaling problem of monocular cameras was not solved. In order to have a full dataset, laps with competitors were included (to have DRS), which made the training harder.

Overall, both families performed quite well. The Visual Odometry did not need any finetuning/training on a particular event to perform well, and has a well known mathematical theory. It however required accurate lens distortion parameters, struggled a lot from the scaling problem (making the velocity extraction impossible), and had small issues generalizing to night races/races with competitors. Deep networks on the other hand performed quite well when finetuned properly, had less noisy results (no need for post-processing) and could be generalized fpr velocity estimation. However, performed slightly worse when applied on a new event, required a complete training dataset and act as a black box.